In today’s blog post, I share the text and images for my talk on Eric Ravilious, which I gave at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery.

In his book The Old Ways the traveller and writer Robert Macfarlane describes the artist Eric Ravilious’ depictions of the Sussex landscape as ‘dreamy watercolours of the prehistoric tracks of the South Downs’. For Macfarlane, Ravilious was an ‘artist of the path’ whose imagination was deeply and profoundly affected by the rolling chalk landscape of the Sussex Downland. In particular, Macfarlane highlights how the ‘soft and equalising sunlight’ and the ‘pathways and the loneliness’ of the South Downs had a particular effect on Ravilious – and the images he produced of this landscape. These aspects of the Downland landscape had such an effect on Ravilious and his art that a close friend observed how he ‘always seemed to be slightly somewhere else’. In today’s talk I want to take you ‘somewhere else’: out on a virtual walk through a selection of scenes of the Sussex landscape, as seen through the eyes of Eric Ravilious. I will be taking a closer look at four images in particular: Furlongs (1934), The Long Man of Wilmington (1939), Cuckmere Haven (1939), Beachy Head Lighthouse (Belle Tout) (1939).

But before I begin properly, let me introduce you to Eric Ravilious. Born in Acton in London, Ravilious moved with his parents to Eastbourne as a young child. Here, the family owned an antiques shop, something that would have an influence on him later in life. He went to Eastbourne Grammar School and in 1919 won a scholarship to Eastbourne School of Art; this was followed by another scholarship to attend the Design School at the Royal College of Art. At the Royal College of Art, Ravilious studied under the renowned modernist artist Paul Nash. Ravilious was also introduced to fellow student Edward Bawden, striking up a close friendship that was to last for the rest of his life. In 1925, Ravilious won yet another scholarship, this time a travelling scholarship to Italy, where he visited Florence, Siena, and rural Tuscany. He also married Tirzah Garwood in 1925 and they went on to have three children. After a brief spell living in Hammersmith, the Raviliouses eventually settled in Essex, initially lodging with the Bawdens at Brick House, and later purchasing Bank House at Castle Hedlingham.

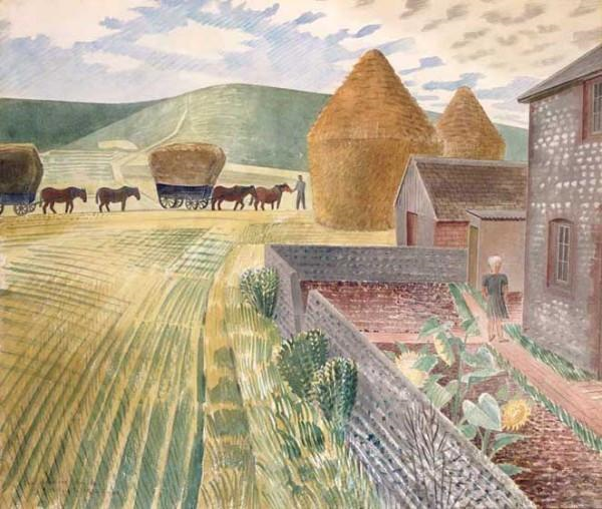

Despite settling in Essex, Ravilious regularly visited Sussex and produced vivid representations of the Sussex landscape as it appeared in the 1930s. In 1934, Ravilious was invited to visit Furlongs, on the Glynde Estate between Glynde and Firle, by the artist and designer Peggy Angus. Here, we can see one of his early depictions of the land around Furlongs, which was – and still is – part of a working farm estate. We can see the house and the corner of the garden on the right of the image. Behind the wall are two hay ricks, and tracking across the centre of the image are two teams of horses pulling hay carts. It is the shape of the Downs behind this rural scene that dominate the background of the image, complete with a track leading up the hill. Amongst the many images of the South Downs produced by Ravilious, tracks are a recurring theme, to quote Macfarlane it is these ‘walkerless paths that entice the eye and the imagination out of sight, promising events over the horizon’.

Between 1934 and 1939, Furlongs became a hub for Ravilious and his circle, including Tirzah Garwood, the Bawdens, his biographer Helen Binyon, the Pipers, Chermayeff, Oliver Hill, Barnett Freedman, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. The cottage at Furlongs had an effect on Ravilious from the moment of his first visit; he described how ‘Furlongs altered my whole outlook and way of painting, I think because the landscape was so lovely and the design so beautifully obvious’. Ravilious loved Furlongs so much that, as Helen Binyon recalled later, he would go on expeditions to junk shops in Lewes and return with items to go in the house. As such the mantelpiece, dresser, and walls of the Furlongs cottage were packed with ornaments, found objects, sketches and paintings. The placing of the ‘junk’ Ravilious acquired for Furlongs was, however, rather eccentric – Staffordshire figurines with a bottle in a basketwork holder, brass lanterns with enamel mugs commemorating various royal coronations.

Ravilious’ visits to Furlongs provided him with an opportunity to explore the landscape around Eastbourne, where he had grown up. For Ravilious these visits enabled him to reminisce and rediscover the South Downs. Indeed, Helen Binyon describes how Ravilious felt that ‘he had come to his own country’. An image that typifies this exploration of the Sussex Downland is his watercolour, The Long Man of Wilmington, painted in August 1939. Here we see a depiction of the giant figure cut in to the northern slope of Windover Hill, on the Downs above Wilmington near Eastbourne. The figure is two hundred and thirty five feet tall and holds a stave in each hand. It was, at one point, thought to be Neolithic or Iron Age in origin but an archaeological excavation in 2003 showed that it was cut in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. In Ravilious’ representation, The Long Man looks like he is cut from the chalk underneath the grass. This is deceptive, as when Ravilious was painting the giant figure, it was actually maintained using bricks. Bricks had been used to maintain The Long Man since a well-meaning restoration project had been implemented by the vicar of Glynde in 1873, the Reverend William de St Croix. In true Victorian fashion de St Croix decided to mark out the outline in yellow bricks, which were whitewashed and cemented together; while he was busy with the yellow bricks de St Croix altered the shape of The Long Man’s feet. Despite the archaeological changes to the hill figure, Ravilious’ The Long Man seems to be a timeless image, a depiction of the English landscape that will not change or mutate. Painted in August 1939, The Long Man represents a fixed point, a calm spell in the face of the gathering storms of the Second World War: Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, mere weeks after this watercolour was painted by Ravilious. The Long Man was soon painted over with green paint to prevent the Luftwaffe from using the iconic landmark as a reference point during air raids and the Battle of Britain.

And now for another iconic image: Eric Ravilious’ Cuckmere Haven, also painted in August 1939. This watercolour depicts the winding, sinuous curves of the River Cuckmere as it flows down the valley to the sea, meeting the English Channel at Cuckmere Haven. Our eyes are led through the image by the meanders of the River Cuckmere, assisted by the paths and tracks on the sides and floor of the valley. What is immediately striking about this image are the colours used by Ravilious. The blue-grey of the sky, the bleached green of the chalk grassland, and the bright blue of the sea in the centre of the image. This emphasises the unique light of the Downland landscape, indeed ‘the paths of the Downs compelled Ravilious’ imagination, and so did the light, falling as white on green, distinctive for its radiance, possessing the combined pearlescence of chalk, grass blades, and a proximate sea’. For anyone with knowledge of the Sussex landscape, Cuckmere Haven is an image that is simultaneously familiar, and uncanny. Like The Long Man of Wilmington, there are aspects of the image that are timeless, for example, the curves of the river and the shape of the valley sides are familiar and, in terms of human time, broadly unchanging. But, also like The Long Man of Wilmington, Ravilious’ painted Cuckmere Haven before it was affected by the Second World War. German intelligence had scouted Cuckmere Haven as a potential landing site; the British army viewed the valley as a potential weak point on the South Coast, particularly vulnerable to invasion. A system of assorted pillboxes, barbed wire, and other large scale defences were installed in the valley, some of which still survive today.

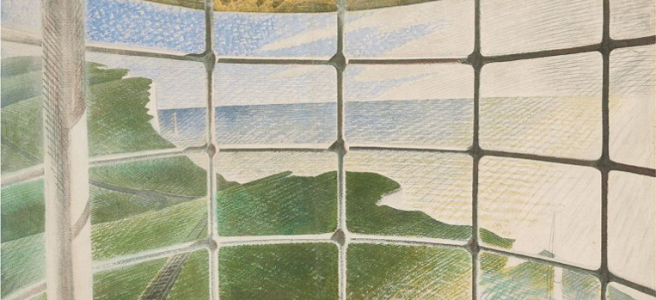

This brings me to the last image I am going to look at today, which is Eric Ravilious’ Beachy Head Lighthouse (Belle Tout), a watercolour that was also painted in 1939. Here, the viewer is standing in the lantern room at the Belle Tout lighthouse, looking out over Beachy Head and the new lighthouse at the base of the cliffs. Belle Tout was built in 1832, the lighthouse was decommissioned in 1902, and by the time Ravilious painted this image it was being used as a private residence. Some of you may remember Belle Tout being moved 17 metres inland in 1999, to rescue the lighthouse from the rapidly eroding and increasingly unstable cliff edge. This idea of edges is important in Beachy Head Lighthouse (Belle Tout), edges and boundaries. The cliffs are a boundary between land and water, and we also have the window, a boundary between inside and outside. In his book The Englishness of English Life, the architectural historian labelled Ravilious as ‘specifically English, highlighting how ‘Ravilious was fascinated by the appearance of human implements in the landscape, depicting in naïve, toy-lie fashion farm machinery, trains, and industrial sites’. And to an extent, Pevsner is right: looking out of the window at Belle Tout, the new lighthouse at the base of the cliffs could almost be a toy, made of Lego or Meccano. It is an idealised view of a new piece of technology in an ancient landscape.

Images of the Sussex landscape painted and drawn by Eric Ravilious present a clean, idealised view of the South Downs in the 1930s. In a period of great change and tumult Ravilious produced timeless, pristine images of a rural idyll based around the rhythms of Downland life. Ravilious’ depictions of the Sussex landscape, like other representations of rural England, are, as the academic Martin Ryle suggests, ‘always half-fantastic images, encouraging the notion that we can identify and preserve an essence of the nation located somewhere else’. This is very apt for an artist that was regularly described as being lost in thought, in a dream-like state – ‘always slightly somewhere else’.

If you are interested in any of the books or images I have used for this blog post, please do get in touch.

Interesring

LikeLike

Really interesting thanks. As a keen runner on the South Downs, I tried to find the location of Chalk Paths last year. Didn’t manage it but read that it might be near Eastbourne at Butt’s Brow although others have suggested otherwise. Have you come across any evidence of its origin?

LikeLike

I’ve not found an exact location, though I have a suspicion it may be up on the hills behind Belle Tout. Comparing Ravilious’ watercolours to the landscape today sounds like a project though!

LikeLiked by 2 people